LOSS OF MASS OR SKETCHES FROM BOMB SHELTERS

Andrii Akhtyrskyi

Online presentation of the exhibition by Ukrainian artist Andrii Akhtyrskyi.

Unfortunately, due to the war, Andrii was unable to join us in person.

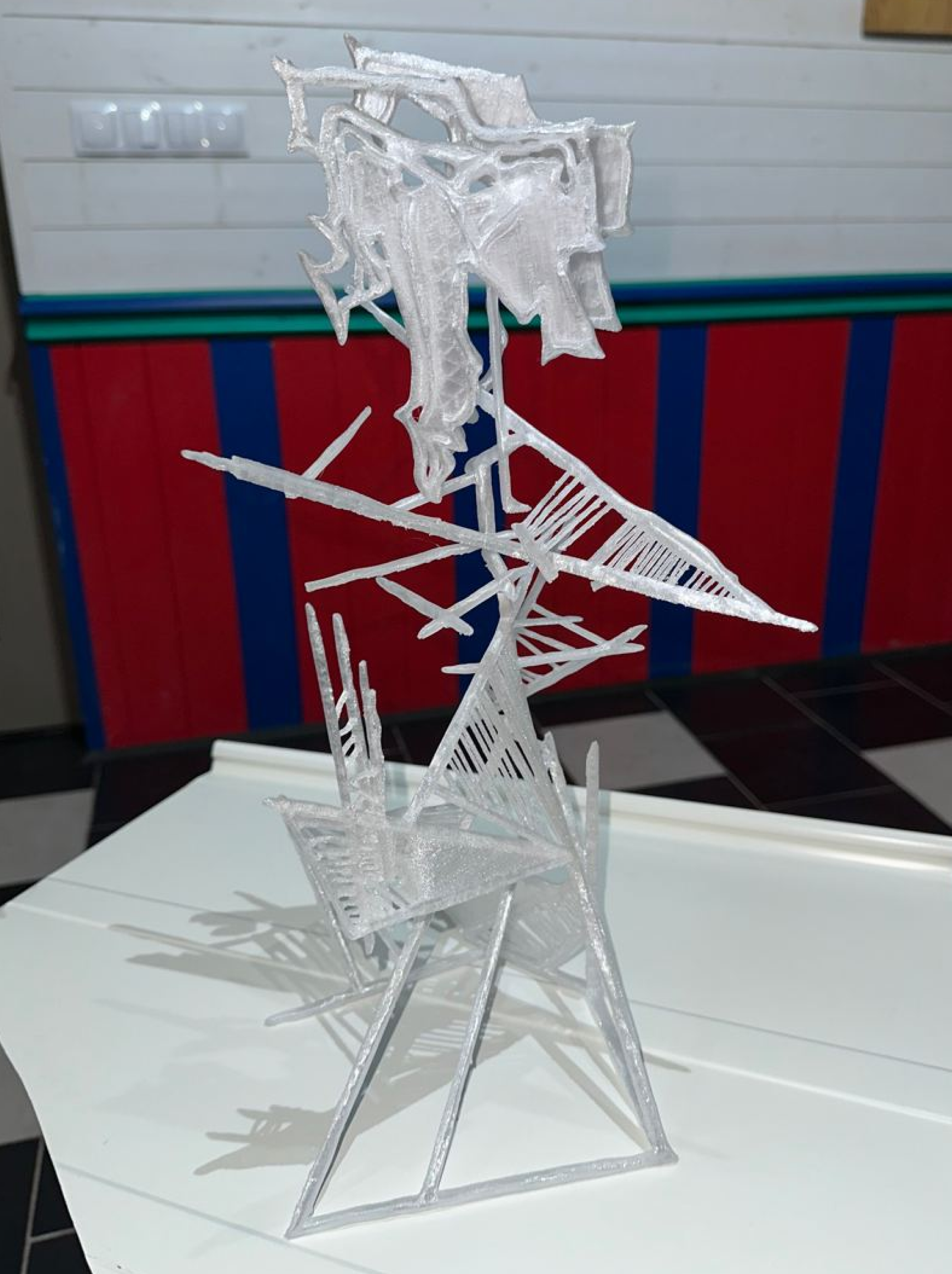

During this time, Andrey shared a series of drawings he’s been creating over the past three years — and throughout the residency — as well as a sculpture that we 3D printed here.

“Loss of Mass or Sketches from Bomb Shelters” is a series of graphic and 3D works created during air raids in a shelter. It’s my visual diary of war — a way to capture anxiety, adrenaline, helplessness, and the attempt to survive through art.

It began with drawings made underground during drone attacks — a way to stay sane and ease the tension. Over time, these sketches evolved into 3D sculptures — virtual, weightless, yet heavy with emotion.

This is a story about loss — of mass, stability, the body, and home. And about new forms of existence born in the dark.

Curated by Uladzimir Hramovich.

︎︎︎ Andrii Akhtyrskyi ︎

Andrii Akhtyrskyi currently lives and works in Odesa, Ukraine.He studied academic sculpture, drawing, graphics, and painting both in art college and at the university.

Unfortunately, due to the war, Andrii was unable to join us in person.

During this time, Andrey shared a series of drawings he’s been creating over the past three years — and throughout the residency — as well as a sculpture that we 3D printed here.

“Loss of Mass or Sketches from Bomb Shelters” is a series of graphic and 3D works created during air raids in a shelter. It’s my visual diary of war — a way to capture anxiety, adrenaline, helplessness, and the attempt to survive through art.

It began with drawings made underground during drone attacks — a way to stay sane and ease the tension. Over time, these sketches evolved into 3D sculptures — virtual, weightless, yet heavy with emotion.

This is a story about loss — of mass, stability, the body, and home. And about new forms of existence born in the dark.

Curated by Uladzimir Hramovich.

︎︎︎ Andrii Akhtyrskyi ︎

Andrii Akhtyrskyi currently lives and works in Odesa, Ukraine.He studied academic sculpture, drawing, graphics, and painting both in art college and at the university.

I’ve known Andrey Akhtyrskyi for quite some time — I even visited him in Odesa back in 2017. I remember how Andrey, not only an artist but also a teacher at the renowned Hrekov Art School (which celebrates its 160th anniversary this year), showed me around the studios, including his own small, cold workspace tucked in the school’s quiet backyard. Thinking back on those moments, it's hard to believe that all that peace and southern calmness now belong to history.

When Russia launched its full-scale war against Ukraine, Andrey was one of the first people I contacted. I don’t know whether it helped him or me more, but our conversations — often during air raid alerts — became a form of mutual support. During one of those “alarm-time” chats, Andrey shared some drawings he had made from the bomb shelter. Here’s what he said about them:

“This series became a personal diary in graphic and 3D form, documenting my internal state and emotional response to life during wartime, interpreting events both at the front and in the rear from an artistic perspective. I began these works during nighttime drone and missile attacks, sketching while sheltering underground — a practice that distracted and calmed me.

As I continued, I realized these drawings weren’t just an outlet for my emotions in the moment — when you hear the sound of a Shahed engine flying overhead, your heart races, adrenaline kicks in, your kidneys activate, you suddenly need the toilet, you sweat. You don’t know where the drone or missile will land. You freeze or go numb. Then, once the buzzing of the ‘moped’ fades, you emerge and try to reset — you start drawing again.

Eventually, I had a full series of these ‘basement’ drawings. They were just meant to help me cope — to switch gears. But I began to notice something in them: a commonality. They started to resemble post-war European sketches, like the battered sculptures of Calder or other 20th-century modernists. And so I had the idea: what if I translated these 'damaged sculptures' into 3D?

Because now, you don’t need to be in a studio to work — you can do it at a computer. And during an air raid, you’re not scrambling to carry messy materials into the shelter. It’s also a way to save resources — materials are expensive now, especially given the near-collapse of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Computer time is limited — you have to sculpt and save before the power goes out.

What’s more, a sculpture can be 3D-printed remotely — in another country, where energy isn’t an issue. Depending on the size, 3D printing can take a day. Or the work can simply be presented as video or 3D projection on a wall. These sculptures gain a kind of mobility and adaptability — something people, especially men in Ukraine, currently lack.”

Since then, this series of drawings and sculptures has continued to evolve, and it became clear that these works deserved to be shown beyond Ukraine. The Mochnarte foundation responded to the idea by inviting Andrey for a short residency and presentation.

Unfortunately, like many Ukrainian men, Andrey wasn’t granted temporary exit permission. That’s why this exhibition is opening without the artist — who remains in a country at war.

For the show, Andrey sent five of his drawings, and I printed the sculpture on a 3D printer myself. The sketches and sculpture genuinely resemble the modernist drafts of a 1970s artist. And if you imagine that’s what they are, then the crucial difference between those hypothetical modernist works and Akhtyrskyi’s is this: he is not working in the postwar period after World War II — he is creating these in the middle of a war whose end is not in sight.

These sketches are “nervous” paraphrases of modernism — or rather, compositions damaged by shelling, torn apart and reassembled, skeletal sculptures that appear broken and rebuilt again and again.

At the Hrekov School, Andrey’s students sculpt from life between air raid sirens. To begin sculpting, as they say, “you have to build mass” — meaning you fill out the frame with clay. “Mass” is also how the explosive power of bombs and shells is measured — the very weapons the teachers and students are hiding from in the cellars of this historic building, which once welcomed avant-garde figures like David Burliuk.

In essence, Akhtyrskyi’s method in this series is not “building mass” but stripping it away — leaving only the skeleton of a sculpture, with all its flaws, as if broken many times and reassembled again and again. Like a body violently losing mass. Like a country losing its people. In the end, we are left with emptiness — or just the contours of possible sculptures — because the “mass” was never gained.

Uladzimir Hramovich

Artist, curator